Some people think they know everything. Others act as if they know, even when they don’t. Strangely, these people often rise faster. But that is where the real danger begins.

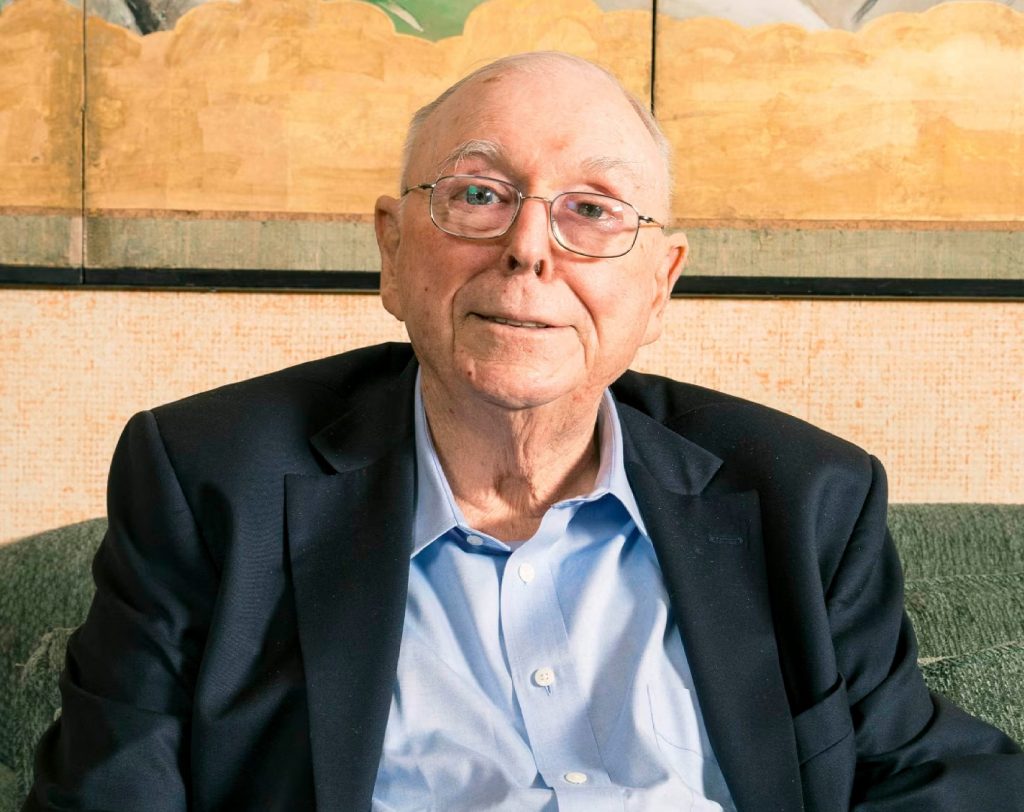

Just last week, Charlie Munger, who passed away at the age of 99, diagnosed this danger decades ago. For many years, he was the partner of Warren Buffett and firmly defended Buffett’s “circle of competence” philosophy, adding this warning:

“You must discover your abilities. If you try your luck outside your circle of competence, you will have a lousy career.”

I recently came across this concept again in Rolf Dobelli’s book The Art of Thinking Clearly. Dobelli, while describing the “illusion of explanatory depth,” says this: The bigger a company gets, the more showmanship, stage performance, and charismatic appearance are expected from its CEO. In such an environment, quiet, creative, careful workers have less chance of standing out. And we fall into the trap of mistaking visibility for success.

Today, the issue of knowing and not knowing has turned into murky water. Thanks to the internet and artificial intelligence, we try a lot, and we touch upon a great many things—at least superficially. A young man on the ferry once told me: “I’ve never read a book in my life. What’s the point? Everything is on the internet.” What I couldn’t tell him was this: finding something in a search engine is not the same as knowing it; copying a text is not the same as understanding it.

Now another young person might ask: “Why should I listen to the advice of a 99-year-old?” Just think about it—this man was born in 1926 and witnessed:

- The childhood scars left by the Great Depression.

- World War II and the post-war reconstruction.

- The Cold War, nuclear tensions, and repeated reshaping of world order.

- The oil crises and inflation spiral of the 1970s.

- The birth of the internet and the revolutionary transformation of access to information.

- The 2008 global financial crisis and the subsequent economic restructurings.

So much change occurred within one lifetime, let alone the past two thousand years. And one distilled lesson from this long, successful life: Know your circle of competence, and stay within it.

Parents enlarge the illusion of visibility geometrically. Everyone thinks their child is a Mozart; the new generation, unfamiliar with failure, grows up with the belief not in a “circle of competence,” but in “you can do everything.”

Yet, in an age of information pollution, perhaps the most radical honesty is to say: “This is outside my circle.”

Maybe the point is not to stay away from fields we don’t know, but to approach them with honesty and a willingness to learn. Saying “this is outside my circle” does not mean closing a door forever; it only reminds us of the need to collect the right tools before passing through that door.

That was the secret of Munger and Buffett’s success: before leaping into unfamiliar territory, they spent time understanding it, measuring risks, and, if necessary, staying away entirely. For wisdom is not only about knowing what you know, but also about knowing what you don’t.

In today’s age of speed, under the pressure of social media and instant consumption culture, admitting ignorance is seen as weakness. Yet true confidence lies not in having an answer to every question, but in being able to say “I don’t know” to the right ones. That is the most solid foundation for both personal growth and long-term success.

Knowing your circle of competence, in fact, demands a kind of intellectual humility. It directs us to respect others’ knowledge and to plan our own learning journey more consciously. And perhaps this is the most precious drop distilled from a 99-year-long life: not mastering knowledge itself, but mastering its boundaries.